Medical student's illustrations featuring Black people, skin tones spark national project

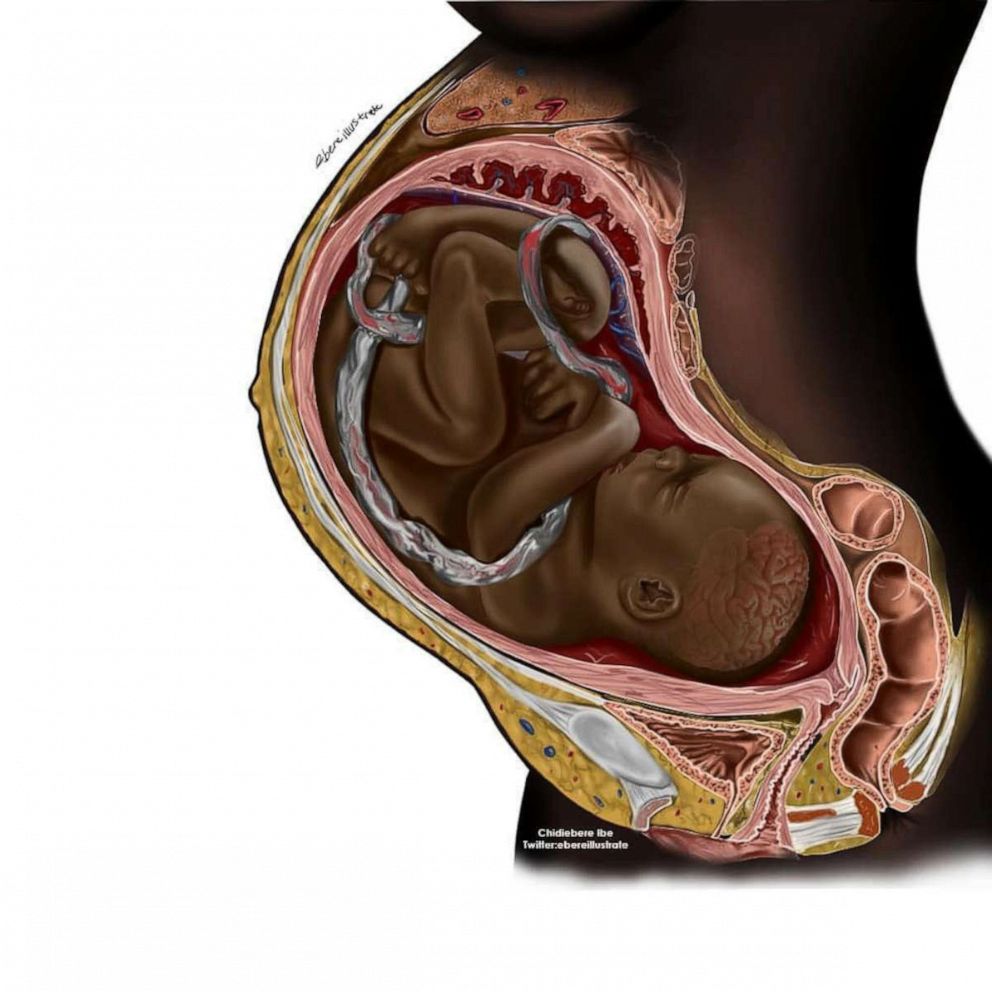

A Black medical student whose medical illustrations featuring a Black pregnant woman went viral in 2021 has sparked a nationwide initiative to diversify images in medicine.

The illustrator is Chidiebere Ibe, a 27-year-old aspiring doctor. One of his illustrations, depicting a pregnant Black woman and her fetus, has received over 100,000 likes on Instagram since it was posted in November 2021.

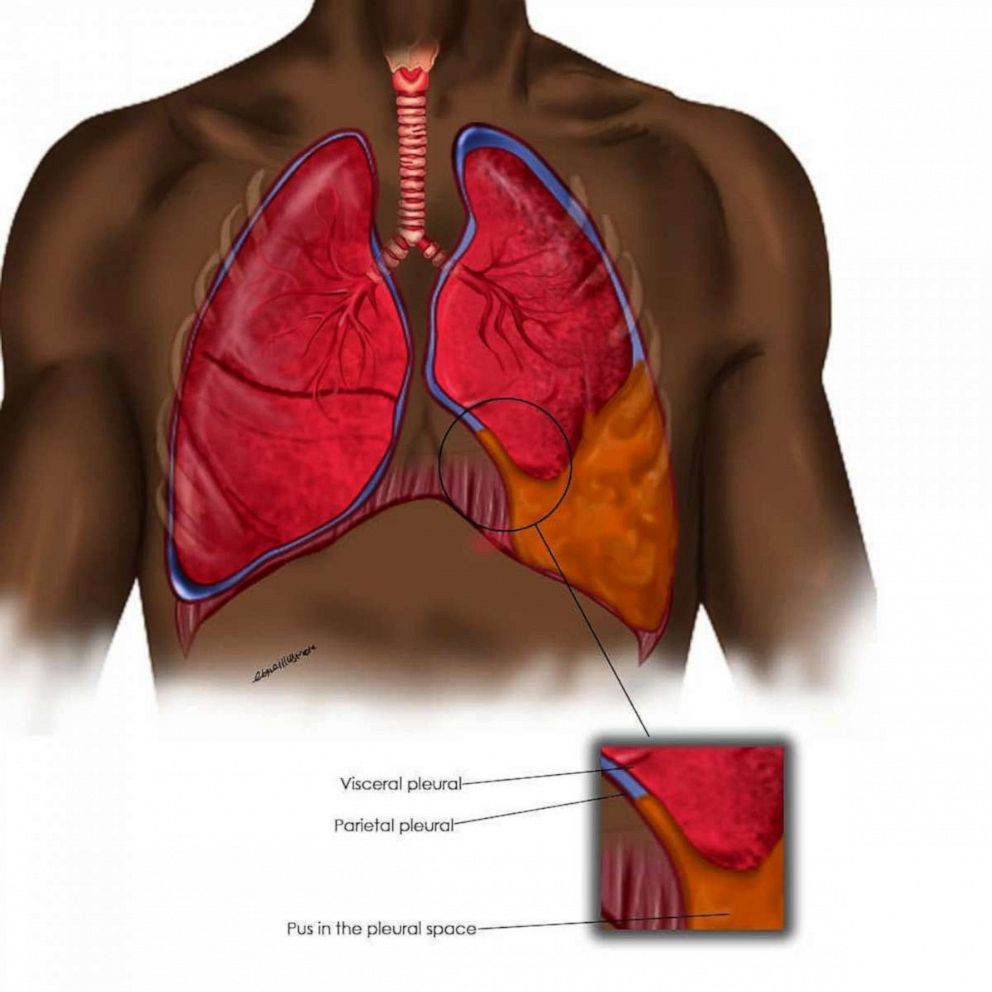

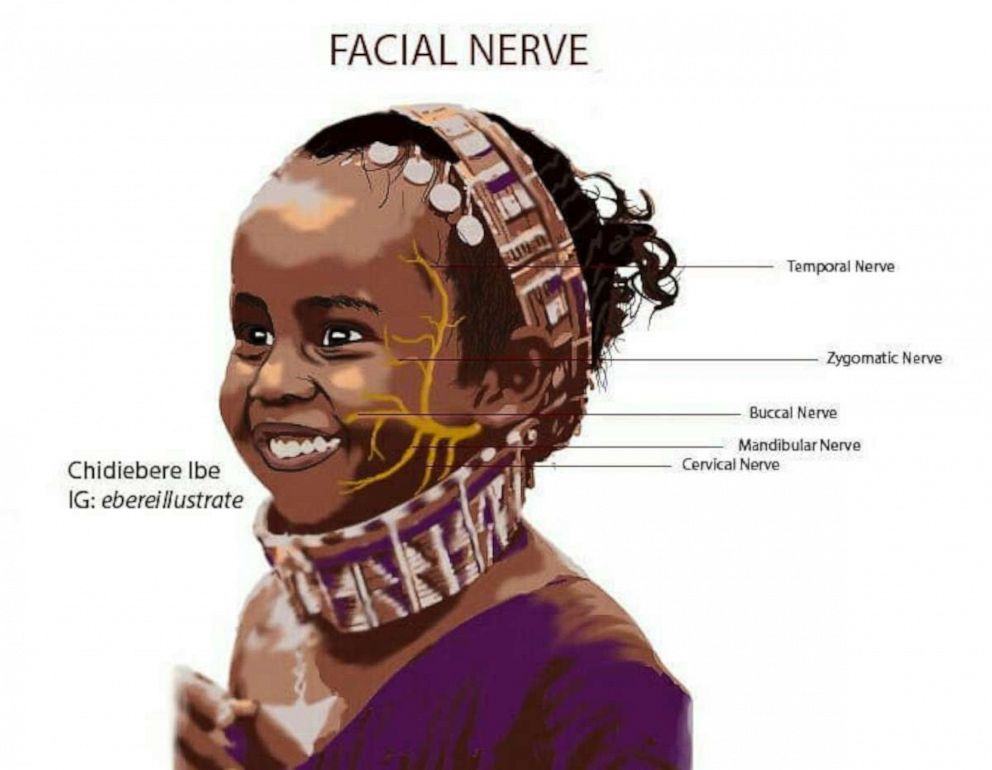

"I'm a self-taught medical illustrator, and I realized that most drawings were not on Black skin," Ibe, who is Nigerian, told ABC News in an interview. "And it became a very big challenge for me."

"When I was drawing something to represent all these key conditions, I needed to have a reference point, and it became very difficult for me, because I could not [find them]," he added.

Ibe's mentor suggested that he create diverse medical illustrations himself, sparking his work to promote diversity in medical illustrations. Ibe is now the chief medical illustrator and creative director for the Journal of Global Neurosurgery and a student at Copperbelt University School of Medicine in Zambia.

"It's now went from being a passion to being a purpose," Ibe said.

Lack of diversity in medical illustrations

Researchers have noted the lack of diversity in medical illustrations. A 2018 study analyzing 4,000 images from four widely used medical textbooks found that while these textbooks approximate the racial makeup of the U.S., they overrepresented light skin tones and underrepresented dark skin tones. The study found that 77% of images showed a light skin tone, 21% showed a medium skin tone, and only 4.5% showed a dark skin tone.

"This is problematic, because the majority of medical imagery consists of decontextualized images of body parts where skin tone is the only phenotypical marker of race," said Patricia Louie, a sociology professor at the University of Washington and a co-author of the study.

"If doctors associate light skin tones with white patients, this may also influence how doctors think about who is a 'typical' patient," she added.

The study also found that when these textbooks depicted skin cancer, they used a white model patient and only showed examples of melanomas on light skin. Louie said that Black Americans are three times more likely than white Americans to receive a late-stage diagnosis for skin cancer.

"This may be because doctors are not trained to recognize how skin cancer presents on darker skin tones," she said.

Rachel Hardeman, a professor specializing in health and racial equity at the University of Minnesota's School of Public Health, connects the lack of diversity in medical illustrations to racism within the health care system as a whole. The lack of representation in medical illustrations, especially in textbooks, she said, is "reinforcing this narrative that whiteness is the norm."

"It's teaching our health care workforce, our future physicians, that the standard and what's 'normal' is whiteness, and everything else is to be compared to that or is different from that," Hardeman said.

Hardeman said that it's pretty uncommon for medical imagery around pregnancy and childbirth to feature Black women.

"My spouse is a physician, and he was like, 'I've never seen that,'" she said.

Louie also said that she saw similar comments about Ibe's work online.

The context around medical illustrations featuring Black people is also important, Hardeman said.

"It's often next to a statistic, such as Black birthing people are four times more likely to experience maternal mortality, or Black infants are twice as likely to experience infant mortality," she said. "It's often tied to these really horrifying and heartbreaking statistics, and rarely is it in a way that's either normalized or celebrated, even."

"As we think about some of the inclusion or the lack of inclusion of Black people or Black bodies in the medical literature, we have to be really intentional about the messages that we are able to send through that work," she added.

'Health care should represent the images of people that we serve'

On June 20, 2023, Deloitte, in partnership with Johnson & Johnson and the Association of Medical Illustrators, announced the launch of a new initiative called Illustrate Change, with the goal to reduce health disparities among people of color, according to a press release.

Ibe, the chief medical illustrator of Illustrate Change, created 25 diverse medical illustrations for the launch, spotlighting darker complexion models and conditions such as atopic dermatitis, prostate cancer, preeclampsia, psoriasis and peripheral artery disease, among others.

"Consider the fact that I created the Black figures, and it went viral," Ibe told ABC News. "It is not OK to say that one image is enough. We need more [images] of people, covering different areas of medicine, and this is why Illustrate Change is a big project, because we are trying to build this library with lots of diverse images that people can have access to."

The medical drawings are available on the project's website, with fellowship applications available for anyone who is interested in contributing to racially aware medical illustrations.

For Ibe, the unexpected virality of his original image, coupled with his involvement in Illustrate Change, gives him high hopes for the medical industry in the years to come.

"We are looking toward improving health care outcomes. So, therefore, the resources used in addressing health care should be diverse," Ibe said. "As health care providers, we are providing care for a vast majority of people … therefore, health care should represent the images of people that we serve."

He added, "I would say that in the course of five years, I really hope that the resources that we use in training our medical students [are] inclusive of the students that we are training."

Editor's Note: This story was originally published on December 13, 2021.